The first thing Ernesto says after picking us up at the train station is that Santiago is the heart of Cuba.

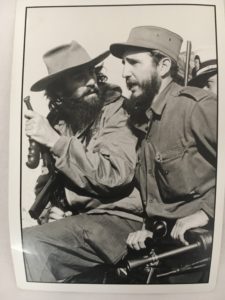

A large port and rail terminal meet at the bay, where a distant Colonial fort overlooks the country’s second-oldest city, guarding the channel. (And where I found a postcard of Camilo with Fidel before entering Havana during the revolution)

We later learn the city is the home of the black Madonna. She resides in a church outside of town that is a major pilgrimage site and sits in front of a mountain where escaped slaves fled.

Also known as Ochún, she’s the goddess of love and femininity, dark-skinned and dressed in bright yellow.

Ernesto, still trying to understand our journey, notes all Cubans are white with a little black or black with a little white, before asking

“And why did you take the train?”

Milena, our next Airbnb host, gets the idea.

“Como Che en moto,” she says, referring to his motorcycle trip across South America before meeting Fidel. Yes, it’s a good way to meet the average Cuban, we tell her, adding that I’m more a fan of Camilo, who I think is like Pete?/George Best, the fifth Beatle.

The bathrooms were nothing more than a stinking metal tube extending up from the floor, I tell

Ernesto later during lunch at a restaurant in a patio overlooking the bay.

He says the Chinese are bringing in new trains.

“The problem is the government never has money for maintenance,” Ernesto says. “Look at the rental cars, they’re the cheapest Chinese cars available.”

Our arrival is just in time for a weekly fair with the narrow streets closed to traffic. A live orchestra in the square plays classical music, and Cuban bands are on the side streets, where historic buildings abound, with plaques detailing its history.

In 1801, the rights of the escaped slaves and others were legalized and they were recognized as free men and landowners.

The Royal Order was read before the image of the black Madonna, also known as the Virgin of Charity. That marked Santiago as the first in the island where the freedom of slaves was proclaimed, 80 years before the formal abolition of slavery.

I chat with Milena about our differences, including race and crime and guns in America, telling her most shootings are drug related, and America is fairly safe. School shootings disturb her and while Cuba is poor, she’s glad she can walk outside whenever she wants and feel safe, something I, as a recent stabbing victim, admit I don’t always feel.

She lives in one of the eight or nine houses her grandfather had before the revolution.

A woman who worked for him lived in the house for years and he was able to sell the others before they were taken. However, he lost a store, a bar and parts of a finca, or ranch, where her father still lives and grows coffee as well as some produce.

A truck owned by her grandfather that was used in the revolution now sits in a museum nearby where he is credited with aiding the rebels.

“He really just wanted them to go,” she said of the donation.

Some of her cousins now live in Europe but others stayed. With Castro’s brother Raul retiring this year, everyone is waiting to see what will happen.

“What Cubans really want is for the blockade to be lifted so we can trade more freely with the rest of the world,” she said.

I settle in to the comfortable house, waste a few 1CUC ınternet cards going online because she has a WiFi router and listen to my new favorite station, Radio Reloj, news bits read off while a clock ticks in the background. The station is the voice of the revolution, it seems, constantly informing the populace of developments across the country and the globe, and it hooks me.

After a day of rest, including mass where the priest stops the process to ensure I am a confirmed Catholic before giving me the host, we enlist Ernesto again and head to the mountains.

Ernesto, who drives a small Peugeot, says decades old Wiley’s Jeeps and Toyota Land Cruisers can cost $40,000 because it’s like buying a business. Milena’s husband later says he’s heard of a new car selling for 250,000CUC,

On the way out, we stop to see the

changing of the guard at Fidel’s tomb, which is smaller than Jose Marti’s memorial just to the left, and is marked by a large boulder with a plaque reading Fidel.

Ernesto later agrees Camilo is the forgotten revolutionary but adds outsiders weren’t responsible for his disappearance in a flight to Havana that never arrived.

“He was the most charismatic of all of them,” Ernesto says. “There’s a story that Fidel was speaking once and Raul and Camilo were in back working. When they came out, the crowd cheered so much for Camilo that Fidel had to stop speaking. Fidel was smart and realized that Camilo was more popular and you know what they say, you can’t cast a shadow on Fidel.”

The car winds it’s way up into the mountain to see the Gran Piedra, past guajiros on horseback out cutting brush for firewood. Little piglets suckling on their mother on the way up, strolling down the street on the way back.

The car goes as far as Ernesto is comfortable taking his livelihood, then it’s a

hike up to the top of the big rock. Then down into the little row of houses and stands to see the coffee plantation started by a French planter who escaped Haiti with 25 slaves. Caught in the rain, we stopped for wood-fired coffee and overpaid, 5CUC for coffee and cigar.

And there it was, a little shack, an iron pot over a wood fire, a cloth coffee filter, a few cigars and some carved wood Orishas. All doled out by a few Yuban who have been in these hills for years, now making up prices for foreign tourists like any other Cuban.